Drone Deployment & Data Defence

Covering Chinese chatters (discourses, narratives, policies and rhetoric) on external events and actors, military and security issues, and India.

Guarding the Great Wall #1: Chinese Military Drones Ecosystem

By Anushka Saxena

The recently concluded 6th Chinese Helicopter Exposition, held in the Tianjin municipality of Northeastern China, put up a colossal show of airpower with over 350 aircraft and air defence systems manufacturers from around 20 countries participating. At this expo, the Chinese People’s Liberation Army Ground Forces unveiled the latest addition to their drone arsenal, the KVD-002, manufactured by the Aerospace CH UAV Company.

Unmanned Aerial Vehicles (UAVs)/ drones have become all the rage in performing a host of defense-related functions, including Intelligence, Surveillance, and Reconnaissance (ISR), ground attack, and countering electromagnetic interference from the enemy. Chinese military policy is paying significant attention to the development and deployment of drones around the world, and is deploying its own ‘Military-Civilian Fusion’ (MCF) strategy to create a drone industry capable of meeting the demands of modern warfare. This also includes equipping drones with autonomous and Artificial Intelligence (AI)-enabled systems, in a quest to achieve the goals of ‘intelligentised’ warfare.

In this context, I am delighted to share with you my latest research document for the Takshashila Institution on ‘China’s Approach to Military Unmanned Aerial Vehicles and Drone Autonomy’.

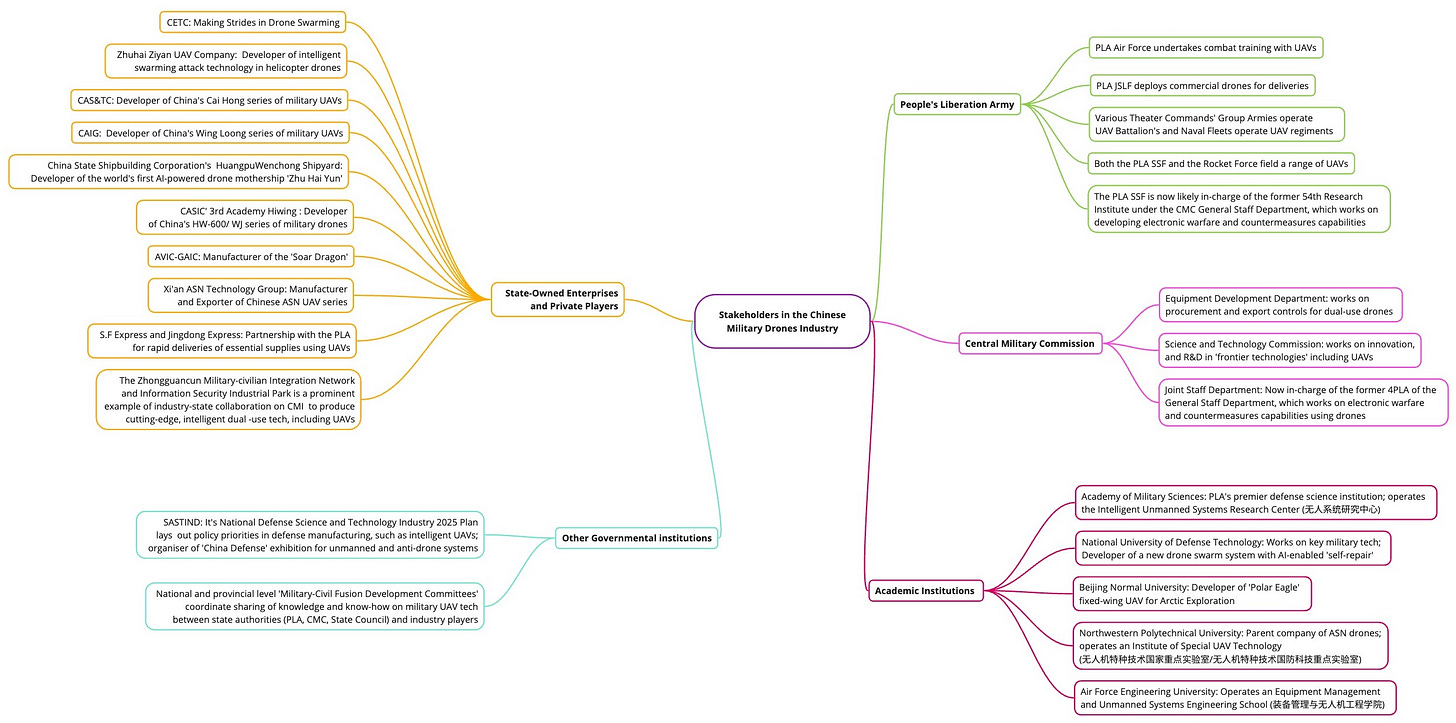

This document assesses Chinese military policy on UAVs and ‘intelligentisation’. It further details use cases of contemporary Chinese drone systems in military training, dogfighting, electronic countermeasures, and ISR, among others. It also identifies some Chinese drone systems with autonomous capabilities. In its annexure, the document discusses drone types and stakeholders involved.

In addition, this document studies drone deployments in the PLA Western Theater Command from an Indian interests perspective, and lays down the structural constraints faced by the Chinese military UAV ecosystem, as well as potential future points of emphasis for China’s efforts in the domain.

Key findings and observations:

Modular drones deployed in the PLA engage in a host of functions, ranging from penetrating Intelligence (electronic and signals), Surveillance, and Reconnaissance (in denied areas), to emitting electronic interference.

For example, China has tested the Aerospace Times Feihong Technology developed FH-95 drone to specifically perform electronic countermeasures (including soft kill measures such as electronic interference and electronic deception), and clear out enemy ‘electromagnetic fogs’ that cause signal jamming.

China has experimented with Manned-Unmanned Teaming (MUM-T) in its deployments within Taiwan’s ADIZ, as well as in the South China Sea and other realistic training scenarios.

In a widely-discussed peer-reviewed paper published in the Chinese journal ‘Astra Aeronautica et Astronautica Sinica’ , authors argued that experiments conducted on a simulation platform indicate that an AI-piloted UAV “not only completes aerial combat tasks in different simulation environments but also outperforms human pilots.” The paper comprehensively considers the advantages of attack angle, speed, altitude, and distance in close-range aerial combat on both sides, and recommends the use of ‘Deep Reinforcement Learning’ to train AI drone pilots in battle tactics.

Drone delivery systems have now become a subject of increased testing by the PLA for the purpose of servicing personnel in tough terrains, such as the mountainous/plateau regions in Tibet, along the border with India.

The PLA-WTC has a UAV battalion with a detachment of CH-5s at the Aksu/ Wensu base in Xinjiang, a UAV Brigade with detachments of drones such as BZK-005 and 006, as well as GJ1 at the Hotan base, and a brigade detachment of UAVs and J-11 fighter aircrafts at the Kashgar airbase just 475 km away from the Karakoram Pass – making it a direct deployment for India to face.

There are two types of high entry barriers to the participation of private industry players in the country's military UAV ecosystem – Technical and Policy barriers.

China's competition with external actors such as India and the United States is impacting the Chinese military drone ecosystem both internally and externally.

With the CMI/MCF strategy at their base, Chinese enterprises working on military drones will likely continue seeking collaboration with civilian drone manufacturers and exporters, to leverage commercial advantage in cutting-edge drone systems and technologies that may not necessarily be available in the military-industrial complex.

‘Smart Swarming’ will continue to dominate the Chinese AI-enabled UAV ecosystem. Chinese state-owned and private entities like CETC, EHang, and Zhuhai Ziyan are now expanding their research and innovation in swarming.

I look forward to your thoughts on this research work!

Guarding the Great Wall #2: CAC’s latest draft regulations on controlling the flow of data beyond borders

By Anushka Saxena

On September 28, 2023, the Cyberspace Administration of China (CAC) released the Draft ‘Regulations for Standardizing and Promoting Cross-Border Data Flow’ (English translation), and is seeking public comments on the document till October 15, 2023.

The aim of laying down these regulations, as stated by the CAC, is “to safeguard national data security, protect rights and interests in personal information, and to further regulate and promote the orderly free flow of data in accordance with relevant laws.”

Here, relevant laws broadly refer to:

People's Republic of China Cybersecurity Law of 2017;

People's Republic of China Data Security Law of 2021;

People's Republic of China Personal Information Protection Law of 2021; and

CAC’s ‘Measures on Security Assessment of Cross-Border Data Transfer’ of 2022.

I would also include the ‘Revised Counter-Espionage Law of PRC’, which came into effect in July this year, under the framework of “relevant laws.”

Despite all of this, the ‘Draft Regulations’ actually aim to ease restrictions on the sharing of some types of data beyond borders. What are these types?

As per clause 1 of the draft,

“Where the export of data in international trade, academic cooperation, or cross-border manufacturing and marketing activities does not include personal information or important data, it is not necessary to make data export security assessment declarations, conclude a standard personal information export contract, or pass personal information protection certification.”

There are no specific parameters detailed in the draft for what constitutes “important data.” However, Article 19 of the above-mentioned CAC ‘Data Transfer Security Assessment Measures’ (which came into effect on September 1, 2022), defines “Important Data.” It reads:

“The term "important data" referred to in these measures means data that, if tampered with, destroyed, leaked, or illegally obtained or used, may endanger national security, economic operations, social stability, public health, and safety, among other things.”

Moreover, an interpretation of clause 2 of the draft can also be helpful here, because it tells us that when relevant governmental departments declare through a public notification or announcement that some type of data is “important data,” then the cross-border flow of such data will have to be put through security measures (making security assessment declarations, concluding a personal information export contract, or obtaining a personal information protection certification).

Other exceptions to data export control measures, as listed in the draft, include:

Overseas provision of personal information that was not collected or produced domestically (clause 3);

Where personal information must be provided overseas as needed to conclude or perform on a contract to which the individual is a party, such as for cross-border purchases, cross-border money transfers, air and hotel reservations, and handling visas (clause 4.1);

Where the personal information of internal staff/ employees must be provided overseas to carry out human resources management in accordance with lawfully drafted labor rules systems and lawfully concluded collective contracts (clause 4.2);

Where personal information must be provided overseas in urgent situations in order to protect natural persons’ security in their lives, health, and property (clause 4.3);

Where it is estimated that the personal information of less than 10,000 individuals will be provided overseas in one year [with the rule that where personal information is provided overseas on the basis of an individual agreement, the data subject’s consent shall be obtained] (clause 5); and

If data being exported abroad does not fall into the specific ‘negative lists’ of Chinese ‘Pilot Free Trade Zones’ [these may independently formulate a list of data (referred to as a “negative list”) that needs to be included under data export security measures] (clause 7).

Clause 8 also provides that “where sensitive information involving the Party, government, military, and units involved with secrets or sensitive personal information are provided overseas, it is to be carried out in accordance with relevant laws, administrative regulations, and departmental rules.”

Thoughts: A joint reading of the terms of this 8th clause, as well as an understanding of the overall cybersecurity and data control atmosphere of China, tells us that things wouldn’t be as simple for foreign firms collecting data from Chinese citizens, as described in the exceptions above.

For example, any decision to export data would not just be governed by this particular set of ‘Regulations’ but a broader spectrum of cybersecurity and personal information laws, including regulations and notifications released by the State Council, the CAC, and even negative lists of the PFTZs (as curated across 20 such Zones in China as of 2022).

…And not all businesses can look to exercise these exceptions. In August 2021, China concluded ‘Critical Information Infrastructure Security Protection Regulations’ on the basis of one the “relevant laws” mentioned above, the PRC Cybersecurity Law. As per article 2 of the Regulations (English translation), ‘Critical information Infrastructure’ firms include “important industries and sectors such as public telecommunications and information services, energy, transportation, water, finance, public services, e-government, national defense science, technology, and industry.” This automatically means that any firm that recognises itself as associated in one of these industries is ineligible to export data without undertaking appropriate security measures.

Moreover, as each and every aspect of governance has become more and more securitised under Xi Jinping, anything can become “important data” at any time, given that it depends solely on the party-state and its judiciary to define its constituents. Hence, I believe that navigating the data export environment China will only become more complex with the adoption of these draft Regulations.

Here, by the way, is a Podcast my colleagues and I recorded earlier this year for the Takshashila Institution’s daily public policy podcast, ‘All This Policy’, on China’s crackdown on foreign firms and the provisions of its revised cyber-espionage law. Do tune in!

Latest from the Indo-Pacific Studies team:

Manoj Kewalramani, Chairperson of the IPS Programme, writes on ‘China’s Vision for a New World Order: GDI, GSI & GCI’: takshashila.org.in/research/takshashila-slidedoc-chinas-vision-for-a-new-world-order-gdi-gsi-amp-gci; and

Amit Kumar, IPSP Research Analyst, writes for The Quint on ‘India-US Ties: Despite Nijjar Storm, All’s Well on the Western Front’: www.thequint.com/opinion/india-us-bilateral-ties-nijjar-killing-canada-justin-trudeau-diplomatic-strategic-partnership.

I would also like to bring your attention to our Institution’s weekly newsletter, the ‘Takshashila Dispatch’ – a compendium to keep you updated about our latest research documents, podcasts, op-eds, and more!