I See You Two Have Met

Covering Chinese policy and rhetoric on external events and actors, military and security issues, economy and technology, and bilateral relations with India.

Greetings!

Thank you for another wonderful year of contributing your readership for ‘Eye on China’. EoC is a free and open-source newsletter, supported by your brickbats and praises. Today, we have a brief edition for you, and we’ll reconvene with fresh perspectives on China in the new year.

In the meantime, if you have feedback and recommendations for us, we’d love to hear from you via anushka@takshashila.org.in. And if you like what you read on EoC, be our Secret Santa, and gift us the opportunity to spread the word in your circles!

Once again, our sincere gratitude, and we hope you have a merry holiday season. With that, happy reading!

India-China Relations #1: The Special Representatives Meet

Anushka Saxena

After exactly a five-year hiatus since December 21, 2019, the 23rd Meeting of the Special Representatives (SRs) of India and China, focusing on the boundary question, finally took place on December 18, 2024. National Security Advisory Ajit Doval, the SR for India, travelled to Beijing to meet Foreign Minister Wang Yi, the SR for China, based on the consensus reached between PM Narendra Modi and President Xi Jinping in Kazan, Russia, on the sidelines of the BRICS Summit on October 23, 2024. It was then specified that the SR talks will resume soon, and only four days before the talks between Wang and Doval was the schedule of the meeting announced.

Both sides affirmed that 6 points of consensus were reached, and that the 24th round of SR talks is likely to happen next year, with Wang travelling to India for the same at a “mutually convenient date.” However, I do not believe there was anything that can be termed a breakthrough of sorts from the meeting readouts from the two sides. In that light, I will restrict this post to four takeaways:

For starters, the two discussed the need to implement the recent understanding reached on October 21 to effectively mitigate differences in the Western Sector of the LAC, and the Chinese have finally come around to calling it a ‘resolution’.

The two sides further agreed to “explore/ seek a fair, reasonable and mutually acceptable solution to the boundary question.” The interesting thing about this phrasing is that it has been around for a long time. It is founded in the Five Principles of Peaceful Co-existence (Panchsheel) and the 2005 India-China Agreement on the Political Parameters and Guiding Principles for the Settlement of the India-China Boundary Question. The inclusion of this phrase in both the 22nd SR talks of 2019 and their 2024 edition indicates that there is, after five years, a willingness to re-invigorate Confidence-Building Measures (CBMs) between the two sides based on the spirit of past agreements. In an environment where mutual trust is eroded due to China’s renunciation of such agreements, this is welcome rhetoric.

India affirmed that the overall political perspective of the bilateral relationship must be taken into account, and that peaceful conditions prevailing on the ground will benefit ties as a whole. In the past four years, India’s policy vis-à-vis China has largely been about not doing business as usual without the settlement of concerns along the seven friction points. Now, with disagreement completed, both EAM Jaishankar’s statement in the parliament on December 3, as well as the SR talks’ readout, have confirmed that India is willing to gradually bring ties across domains back to (a new) normal. But, the unchanged fact still remains that peace on the border is indeed a precondition to overall peace. This is evident from the Indian readout’s expression that there is a “need to ensure peaceful conditions on the ground so that issues on the border do not hold back the normal development of bilateral relations.” From Beijing’s readout, too, it is evident that the Chinese narrative on “placing the border situation in its rightful place in bilateral relations,” remained intact.

Finally, as always, the FMPRC readout did not discuss the consensus on opening up the Kailash Mansarovar Yatra, data sharing on trans-border rivers, and border trade, which have, over time, always found mentions in Indian readouts. Interestingly, however, a Global Times article discusses a consensus on these fronts between Wang and Doval, stating:

Both sides agreed to continue enhancing cross-border communication and cooperation, promoting the resumption of pilgrimages by Indian pilgrims to Xizang, cooperation on cross-border rivers, and trade at the Nathu La Pass.

Overall, the meeting was a great step ahead in kickstarting high-level dialogue between the two neighbours after four tumultuous years. However, the big challenge here, is the part about “injecting more vitality” in the SR process – which was also apparently agreed upon between Wang and Doval. The SR process is meant to firm up solutions to the boundary question, but hiatuses such as the one that ended this month are uncalled for. Not only do these disrupt communication, but also enable China to change the status quo over a prolonged time by erecting permanent settlements and villages, and stationing troops and heavy weapons systems. In that regard, SRs are uniquely positioned to continue high-level engagement even as there are vagaries in the overall bilateral relationship, while also ensuring historical and more structural issues in the India-China dynamic, especially the border, continue to be revisited and addressed.

India-China Relations #2: Takshashila’s Latest Survey Report

Anushka Saxena

I am delighted to share Takshashila’s latest Survey Report, ‘Pulse of the People: State of India-China Relations’. The 2024 Report discusses the Indian public's opinion on key economic, technological, political, and security issues pertaining to India and China.

When India gained independence in 1947, it inherited the British policy on the status of Tibet, as well as the McMahon line – the border between Tibet and India. With China’s annexation of Tibet in the 1950s, India and China became neighbours for the first time, and while India accepted China’s claim over Tibet, differences over the McMahon Line continued to impinge on the relationship, eventually resulting in a major turning point in bilateral relations – the war of 1962. The diplomatic relations frozen in the aftermath of the war began to thaw in the 1970s. However, it was only in 1988 that the two sides embarked on a new phase of normalisation. Subsequently, they inked a series of bilateral agreements and understandings to govern the LAC. The peace held till 2020, barring frictions and clashes in 2013 (Raki Nala), 2014, 2015 (Burtse), and 2017 (Doklam).

In the past few years, India-China relations have been transforming dynamically. In the aftermath of the deadly clashes that erupted on the Line of Actual Control (LAC) in 2020, India’s China policy has become highly oriented towards security. This is especially manifest in India applying a national security lens with regard to imports, technology, investment, and talent from China. This has, of course, not translated into an improvement in India’s trade balance with China, with the trade deficit crossing the US$ 100 billion mark in FY 2021-22.

More recently, however, the two countries have attempted to engage diplomatically and achieve stability in the border dispute. A new agreement disclosed on October 21, 2024, revives India’s access to patrolling and grazing rights in the Depsang and Demchok regions, restoring them to the pre-2020 stand-off status. The agreement has spelled optimism for bilateral engagement on the boundary question.

But beyond the immediate crisis triggered by the standoff in Eastern Ladakh, there are structural, underlying issues creating friction in the bilateral relationship, such as India’s support for the Dalai Lama, and China’s friendship with Pakistan. In addition, India’s expanding relations with the US and participation in groupings like the Quad are also significant factors in the India-China relationship.

In general, the sentiment toward China among the Indian populace appears to have become quite negative since 2020. But, what do Indians actually think about India-China relations, and the trajectory of India’s China policy going forward? How do the people expect the Indian government to react to key events that may emerge in the near future? The Takshashila Institution’s 2024 Survey report, ‘Pulse of the People: State of India-China Relations’, attempts to address these pertinent questions.

The Survey questionnaire captured data on 11 substantive inquiries pertaining to India-China relations, from over 600 respondents, over a period of two months. A majority of these respondents (391) are between 30 and 60 years of age, followed by the second biggest group of respondents (219) aged 16-29. Most respondents affiliate with the private sector (242), and the second biggest groups are students (125) or employed with the armed forces (122). Their responses have yielded some vital results: many confirmatory, and some counterintuitive, that can together serve to inform policy.

We believe the Survey has the potential to act as a springboard for future research, while also inspiring thought for not just the academic reader, but also for public and private sector professionals, think tanks, and civil society. It is also intended to be a periodic Survey so that we may be able to study variations in response patterns on the same issues over the years.

Some key takeaways:

A majority of respondents (54.4%) shares the sentiment articulated by the Indian Ministry of External Affairs, that the boundary dispute along the Line of Actual Control (LAC) is at the front and center of the current tensions in India-China relations.

A notable group (26.6%) also believes that China’s inroads and influence in India’s neighbourhood is the second-most vital stressor in the bilateral relationship, which is a surprising result, with respondents according lower significance to more visceral factors such as China-Pakistan friendship, India-US partnership, and a massive trade asymmetry favouring China.

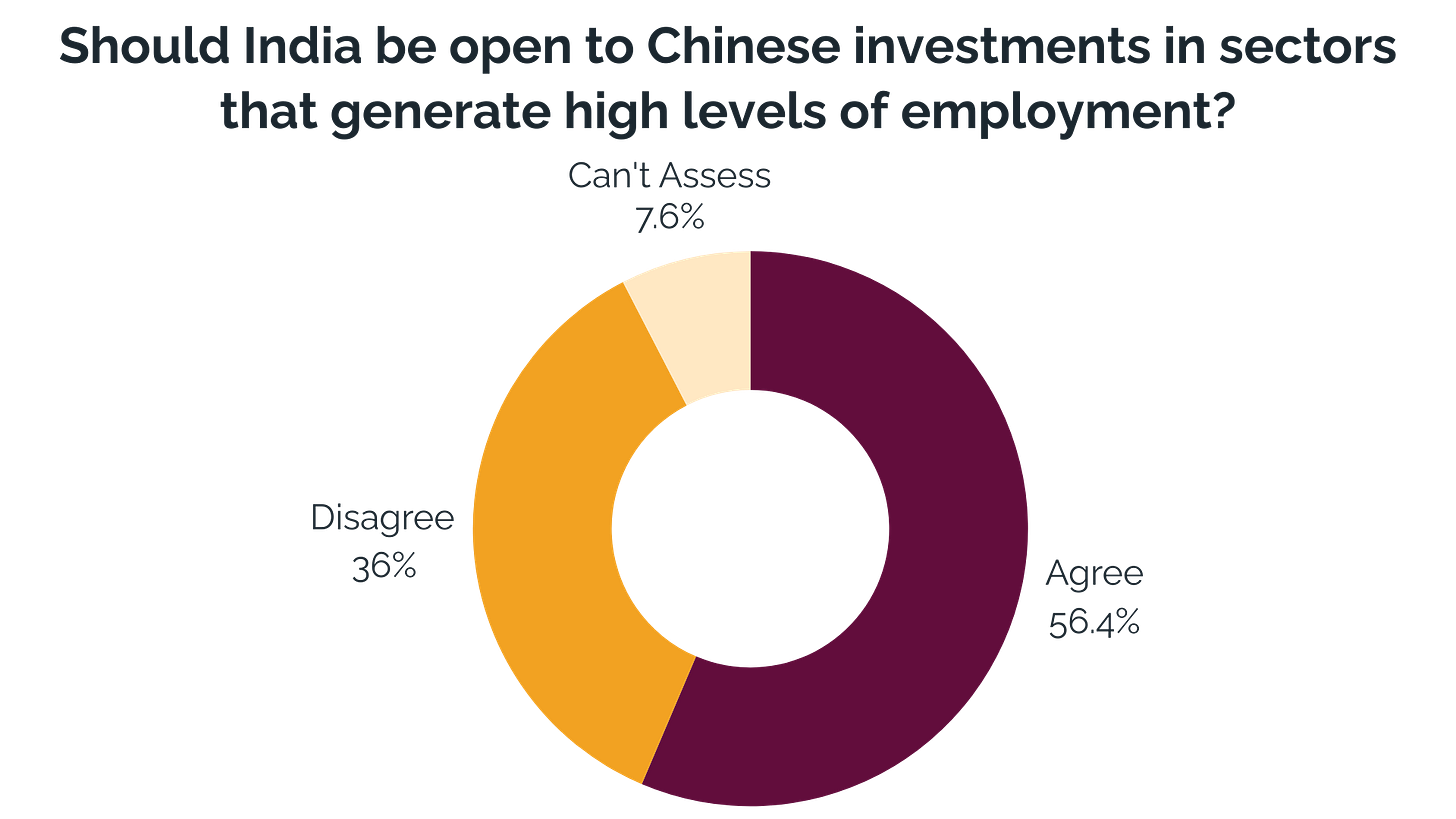

Regarding the 3 key aspects of bilateral economic relations, namely trade, talent, and investments, respondents have expressed a positive attitude vis-à-vis India’s greater engagement with China. A majority of them agree that greater trade with China is in India’s developmental and security interest (49.6%), and that investments from China are beneficial, especially in sectors opening up new employment opportunities for Indians (56.3%), and that Chinese talent should be welcome in India, if requisite Indian talent in a particular industry is lacking (52.4%).

The Survey asked respondents whether ties with China would have been better had President Xi Jinping not been in charge in Beijing, and if China had been a multi-party democracy similar to India. Interestingly, a vast majority (61.5%) believe that if the Chinese political ecosystem was more democratic, with multiple political parties contesting for leadership and power, India’s relations with China may well have been better.

However, many expressed uncertainty (46.6%) that if anyone other than Xi were leading China, India-China relations would be better. This indicates that there is a belief that the trajectory of the relationship between the two rising neighbours is bound to be difficult regardless of the leader in power in Beijing.

The Survey also assessed the respondents’ understanding of how external stakeholders and scenarios impact and relate to relations between India and China. Overwhelmingly, a majority of the respondents (69.2%) believe that if forced to choose, India must align closely with the US-led West, and not the China-Russia axis.

However, a majority also believe that the Quad, which is a grouping of India, the US, Japan, and Australia, has only been somewhat effective (50.8%) in countering China. Many respondents (44.4%) even see it as “ineffective” in this regard.

On two key ‘red lines’ China perceives as critical to its territorial integrity, national security, and ideological stability – the issues of Tibet and Taiwan, respondents weighed in to suggest India’s policy options. When asked what India should do if both Beijing and the Tibetan Administration-in-Exile in India nominate their own successors to the current Dalai Lama, an overwhelming majority (64%) expressed support for the latter nominee. A minority believes that India must recognise neither (17.9%).

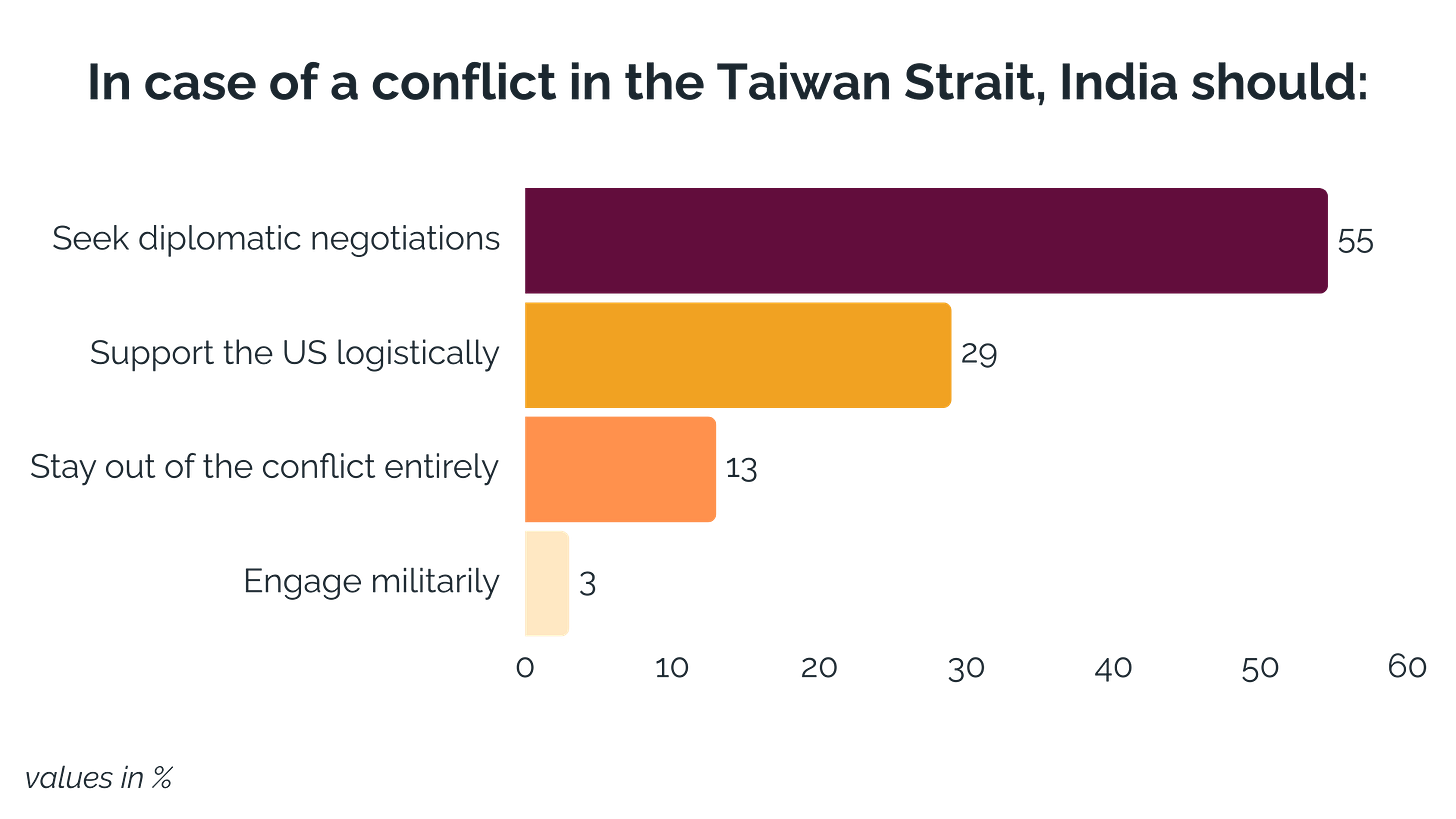

In the case of a Taiwan Strait conflict, however, attitudes are more moderate, with only a small minority (3.5%) suggesting that India get involved militarily. A larger number (28.7%) argued that India should support the US logistically in such a conflict. While some respondents (13.3%) may have advocated India has no role to play in this conflict, the overall response pattern suggests greater awareness of the regional fallout of a conflict in the Taiwan Strait. In this light, most respondents said that India should play the role of a peace-broker (54.4%), encouraging diplomacy and negotiation toward a peaceful resolution.

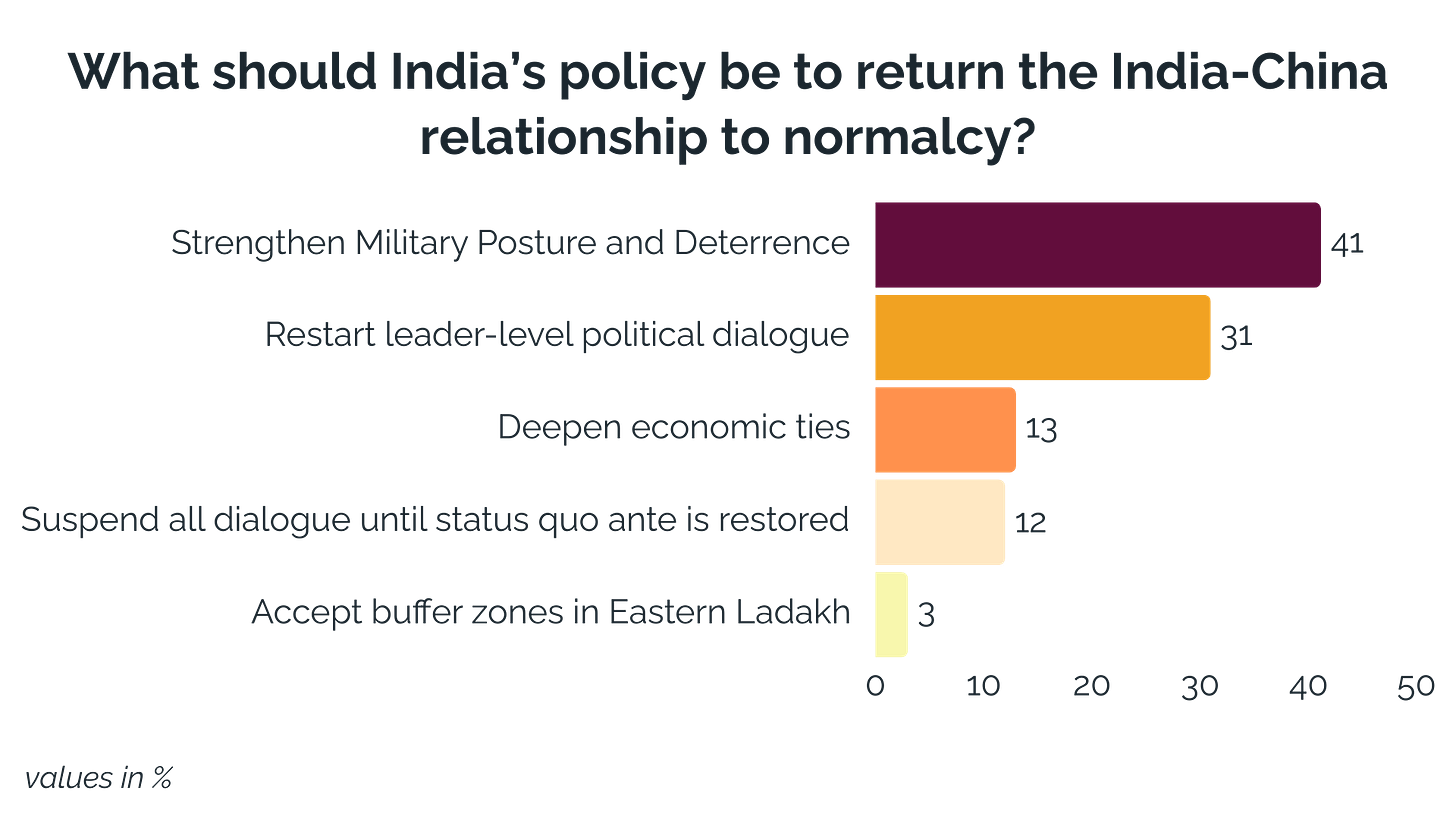

Amidst intense deliberations surrounding a solution to the ongoing tensions in India-China relations, the Survey also assessed the respondents’ opinions on the best way forward. Strengthening India’s military posture and deterrence (41.2%), and at the same time, re-starting high-level political dialogue at the level of leaders on the two sides (31%), have emerged as the two most popular policy suggestions.

The full report is available here for anyone interested in uncovering the complete dynamics of the response attitudes, and our analyses on them.

Also, the Report was launched at Bangalore International Centre on December 17, 2024, and a panel discussion on ‘A New Modus Vivendi with China’ was held to chart out the ‘new normal’ in India-China Relations. Tune in to the event proceedings here:

More of Takshashila’s Pioneering ‘Thought-letters’:

If deep-diving into Quad and Indo-Pacific-related developments is something you like to do at least once a week, check out the Quad Bulletin!

Your regular dose of all things technology geopolitics, with a particular focus on the technological potential of India, awaits you in the Technopolitik newsletter!

The Takshashila Geospatial Bulletin is a monthly dispatch of Geospatial insights for India’s strategic affairs. Gear up for a visual journey!

If you’re curious to learn more about Takshashila’s work in general, and read fascinating stories, subscribe to the weekly Takshashila Dispatch!

Latest from the Indo-Pacific Studies Team:

Appearing on StratNewsGlobal’s interview show, ‘The Gist’, Manoj Kewalramani discussed the current state of India-China relations and what his takeaways are from the meeting between the Special Representatives (SRs) on the Boundary issue on both sides. Tune in:

In her latest commentary for Hindustan Times, a widely read Indian daily, Anushka Saxena discusses the recent developments indicating ‘Power Shifts in China’s Defence Establishment’.

Rakshith Shetty’s latest discussion document for Takshashila is a comprehensive study of India’s Critical Minerals Policy and Strategy.

Further, in the latest episode of ‘All Things Policy’, Takshashila’s daily public policy podcast, Rakshith Shetty and Anushka Saxena discuss India’s policy approach to critical minerals based on the findings of the document, and the ‘China challenge’ that lies therein. Tune in for more: